On March 21, 2022, a Federal High Court in Calabar acquitted and discharged Agba Jalingo, after a marathon trial of the journalist which lasted 30 months in what is a classic case of strategic lawsuit against public participation (SLAPP).

Justice Ijeoma Ojukwu, presiding over the court, dismissed all charges of treasonable felony, terrorism, and cybercrime brought against the journalist by the government of Cross River State. It was one of the longest judicial odysseys in Nigerian press history.

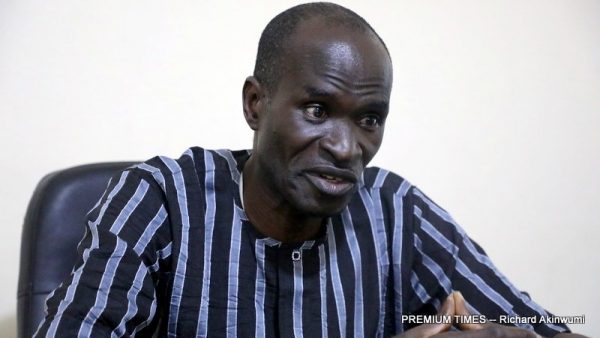

Agba Jalingo, the publisher of Cross River Watch online newspaper, was arrested by police at his Lagos residence on August 22, 2019, and taken into custody. He had been summoned to meet the police in Lagos on August 26. In their summon, the police had accused him of “conspiracy to cause unrest” and “conduct likely to cause a breach of peace.”

The journalist had published an article demanding accountability for public funds earmarked for a bank project which was not delivered by the Rivers State Governor, Benedict Ayade.

“Whether for the accountability story regarding the bank project or for supporting the #RevolutionNow protests, Jalingo’s arrest and detention are an arbitrary and flagrant abuse of his rights as a journalist,” the Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA) condemned the harassment of the journalist.

Charged in a Federal High Court in Calabar with treasonable felony, terrorism, and attempt to topple the Cross River State Government, Jalingo was remanded in custody and twice denied bail. On his second appearance on October 4, 2019, Jalingo was shoved into the courtroom handcuffed like a common criminal.

In an episode that offends the most basic principles of fair trial, the presiding judge, Justice Simon Amobeda, during another session on October 23, 2019, ruled to allow witnesses to testify against the accused without disclosing their identity.

Justice Amobeda was forced to recuse himself after a recording of his private remarks about the case was leaked. The remarks were judged prejudicial against Jalingo, leading to a flurry of protests against the judge. The journalist was eventually granted bail on February 17, 2020, having spent 179 days in detention. After his release, Jalingo alleged that, at a point, his two hands were chained to a deep freezer for more than two weeks.

Welcoming Jalingo’s release, the MFWA said “The entire process represents a blatant case of abuse of power to intimidate and silence a critical journalist.”

The trial subsequently suffered several adjournments and the charges were amended several times.

“Their intention was to scare me, push me until I break. So the lesson I have learnt is that it is better to hold on,” Jalingo told reporters after Justice Ijeoma Ojukwu dismissed the case.

“It’s just painful that our system is skewed in this manner where three years of my time has been wasted coming from Lagos to Calabar because of a sham trial,” he added.

The dismissal of all charges levelled against Jalingo is the second milestone victory the journalist has won amidst his ordeal. On July 9, 2021, the ECOWAS Court of Justice ordered the Nigerian government to pay the persecuted journalist the sum of 30 million naira (USD 73,000) in compensation. The court ruled that the state subjected him to dehumanising treatment while in detention.

“We have looked at the evidence before us. There was no answer as to the facts that Jalingo was arrested and illegally detained, brutalised and dehumanised. This is against international human rights treaties, particularly the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights to which Nigeria is a state party. The Nigerian government has flouted the provisions of these treaties on international fair trial standards, the ECOWAS Court, in Nigeria’s capital Abuja,” said in its judgement.

Jalingo’s case typifies a sad phenomenon of arrest and prosecution of journalists on frivolous charges in Nigeria. In a pattern that underlines the pettiness of these legal actions, most of the cases linger for months, even years before they are struck out, abandoned, or settled often with the acquittal.

One journalist whose case underlines this trend is Oliver Fejiro, founder of the Secret Reporters online newspaper who has been embroiled in a legal battle for the past five years. Arrested on March 16, 2017, in Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, over a series of articles alleging corruption at a local bank, Fejiro was arraigned before a Federal High Court in Lagos on April 28 on cyberstalking charge, and released on bail on May 11, 2017. Five years down the line, the case has yet to be decided. The journalist told the MFWA in a recent chat that the next hearing is scheduled for September 2022.

Another journalist, Luka Binniyat, was detained for 84 days before being granted bail by a Federal High Court in Kaduna on January 27, 2022. Binniyat, a reporter for the US-based Epoch Times online newspaper, was arrested on November 4, 2021 after he wrote an article denouncing the Kaduna State government’s indifferent response to attacks by bandits on communities in southern Kaduna.

Binniyat told the MFWA that immediately after his release, the authorities revived a different case that has been dormant for the past two years.

“Just about a month after I was granted bail, I received notice to appear in court in connection with another case that has not been called for two years. The authorities are bent on persecuting me into silence,” Binniyat told the MFWA.

That case dates back to 2017 when he was charged with publishing false news. As correspondent, Kaduna State Correspondent of Vanguard Newspaper, Mr. Luka Binniyat, had authored a story about the alleged killing five students of a College of Education in the State. He later retracted the story after he realized his sources had misled him.

The emblematic case of Jones Abiri, the editor of the Weekly Sources newspaper, encapsulates the Nigerian authorities’ brazen resolve to SLAPP journalists into submission. The journalist was arrested in 2016 on accusation of carrying out terrorist activities and was to spend the most part of the next two years in detention amidst an intense campaign against his persecution. For instance, the Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA) joined twenty other press freedom and human rights organisations across the world to petition President Muhammadu Buhari to ensure the outright release of Abiri and to sanction his abusers.

In another case of pointless prosecution, the SSS (formerly DSS) arrested Kufre Carter, a journalist with XL 106.9 FM, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, on April 27, 2020. This followed the leaking into the media, including social media, of the journalist’s critical comments about the state Health Commissioner’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. Carter was arraigned before a Magistrate’s Court in Uyo on defamation and conspiracy charges, remanded, and released after a month. The prosecution failed to appear for several sittings until the case was struck out on November 22, 2020.

The judicial harassment that these journalists have suffered are but a few examples of frivolous, legal actions initiated by powerful people in order to silence critical journalists in Nigeria. They point to a growing trend of malicious legal proceedings against journalists in that country. These are desperate, often face-saving efforts aimed not really at refuting critical publications, but at deflecting attention from the ensuing scandals and, more importantly, at harassing the journalists involved. These are lawsuits initiated in bad faith by the complainants who normally do not expect to win, but seek to intimidate and unsettle the accused journalists.

In most cases, SLAPP suits do not travel the full distance but are abandoned along the way or left to hang over the head of the defendants like the Sword of Damocles. They usually drag for months, even years, in an often deliberate scheme to distract the defendants from their work, drain them psychologically and financially, thus intimidating them into self-censorship. A further objective is to deter other journalists from daring to produce any punchy publications about the plaintiffs or the subject in question. The deliberate delays, often through lack of cooperation by the complainants/plaintiffs, call into question the impartiality and independence of the judiciary, if not its efficiency.

Though not an exhaustive list, the cases cited here bear the classic hallmarks of SLAPP. They underline an endemic culture of hostility to critical journalism among powerful people in Nigeria. What is more depressing is the fact that all the above actions are criminal rather civil proceedings.

The situation is delicate. At the core of it are competing needs and rights. There is the need to hold journalists accountable for disinformation and libelous publications. There is also the right of the public to receive factual information. Both considerations are undermined when journalists fear to report on certain sensitive issues of public concern or fail to do due diligence before publishing their stories.

It is therefore imperative to find the right balance in protecting the reputation of individuals from wanton attacks, while safeguarding press freedom and the public’s right to information at the same time. It is in this regard that most jurisdictions have abolished criminal libel and tend to discourage adversarial legal actions in favour of mediated settlement of press-related litigations.

SLAPP suits constitute a daunting threat to press freedom and democratic participation. There is the need for the judiciary and the state prosecutors to be sensitised on the malicious nature of SLAPP actions to be able to discern their underlying artificiality and impact on press freedom. When it becomes obvious that their clients are being subjected to SLAPP, lawyers must point it out and argue forcefully for judges to strike out or dismiss such cases. While the MFWA condemns the growing cases of long detentions and subsequent frivolous suits against journalists, we also call on journalists to observe the highest professional standards and uphold the public interest at all times.