The Gambia goes to the polls on December 4 as a beaming light of hope for press freedom and democratic governance in a West Africa region where such ideals are fast dimming.

The region, previously touted as a poster child of democratic governance and freedom of expression when compared with the other regional blocs on the African continent, is quickly running out of examples. Senegal, long praised for its democratic credentials, has in recent times recorded disturbing incidents of abuses underlined by the March 2021 killing of protestors, social media disruptions and shut down of media houses. Ghana, its counterpart, has lately been scoring low on press freedom, underscored by the 2019 killing of investigative journalist, Ahmed Suale. Most of the other countries in the region are performing worse with Mali and Guinea plunging back into military rule.

The Gambia heads into the polls with a different narrative from its compatriots in the West Africa region. For many years the country was noted for the atrocious crimes perpetrated against journalists, opposition leaders and dissidents by its despotic leader, Yahya Jammeh. The story has been different in the last five years following the end of the Jammeh regime. The Gambia has made tremendous progress in freedom of expression and democratic governance. The upcoming presidential elections could either add more to the gains or dissipate them.

Improving press freedom credentials, media landscape whip interest in polls

The country has moved from the 143rd position in the global rankings on press freedom by the RSF during the last elections in 2017 to a tremendous 87th position in the 2021 rankings. This improvement has been accompanied by rapid numerical growth in the media landscape with many privately radio and TV stations springing up and reporting issues surrounding the elections from diverse angles. The development has whipped up euphoric interest in the electoral process. The situation is contrasted with elections in the Jammeh regime where state-owned radio and TV had broadcast news monopoly.

“We have a lot of media houses now. During those periods [Jammeh regime], if you can recall, the people didn’t care about current issues; they just focused on entertainment. But now everybody is there in the media landscape,” Mohammed Ba, Vice President of Gambia Press Union, said in an interview with the Media Foundation for West Africa. “Everyone claims to be a journalist and they are inviting politicians to have discourse about the elections.”

The media and journalists are not only buoyed to facilitate the conversation about the polls, but they also have the assurance that they will not be arrested for doing that work, Mr Ba added.

“There are no threats. People feel the government is not going to interfere. People are using current issues to generate political discussions and they are also inviting opposition parties. But then it was a taboo to invite opposition. They might even come and pounce on your media house sometime in the morning or evening, arrest or tell you to go off-air. These are things are not happening now,” Mohammed Ba said.

According to a 2021 Afrobarometer study, 82% of Gambians think the media is completely or somewhat free to do their work without interference or censorship by the government.

Indeed, on November 22, The Gambia hosted its first presidential debate. The debate afforded the candidates the occasion to expound on the policies and programmes they intend to implement when elected and as well critique the incumbent government’s performance and policies. The electorate was afforded the rare opportunity of raising critical questions to the candidates. Even though only two of the six candidates cleared to contest participated in the debate, the organisers, the Commission on Political Debates, considered it a success given its novelty.

The newfound freedom in the Gambian media landscape is the result of many pivotal decisions and developments. Key among these developments is the Supreme Court’s ruling as unconstitutional, the criminal libel law of the country, the compensation paid to the Ebrimah Manneh and Deyda Hydara, two journalists who were killed during the Jammeh regime, and the recent passage of the access to information law.

Nonetheless, as the media landscape improve, there have been concerns about the partisanship, coverage bias and unfairness among some of the media houses leading to the elections. The state-owned media has particularly been noted.

“The state-owned media is still bias. What we expected was a level-playing field to ensure that all political parties have access to the state-owned media. But the problem is still there. There’s a trend. The President is still the face. They used to do certain newspaper reviews we had some kind of critical balance reporting but now the state media is not doing it anymore,” Mohammed Ba said.

The private media, despite the vibrancy they have added in the reportage, is also a culprit of the biased coverage.

“It happens mostly to the online media houses. For instance, Kerr Fatou has been nicknamed as Kerr UDP [the leading opposition party] meaning they are mostly in line with the UDP while sometimes Fatou Network, another online media house, also accused of being pro-NPP [the governing party],” Sait Matte, Executive Director of Center for Research and Policy Development in The Gambia, told the MFWA.

Mr Matte, however, believes the media houses are making great efforts to ensure balance despite the perceived bias.

Threats of old laws and seeming hardship

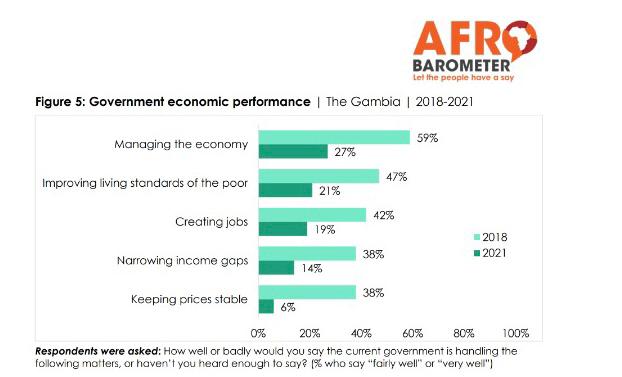

The progress in media freedom and human rights are perhaps among the only few steady developments the Gambia have witnessed in recent years, as 60% of citizens believe the country is heading in the wrong direction. This is contrasted with 2018 when only 29% said the country was going in the wrong direction.

Citizens who believe the country’s economic conditions are good have reduced from 58% in 2018 to 25%. Similarly, the number of citizens who believe their personal living conditions are good have also reduced from 66% to 35%.

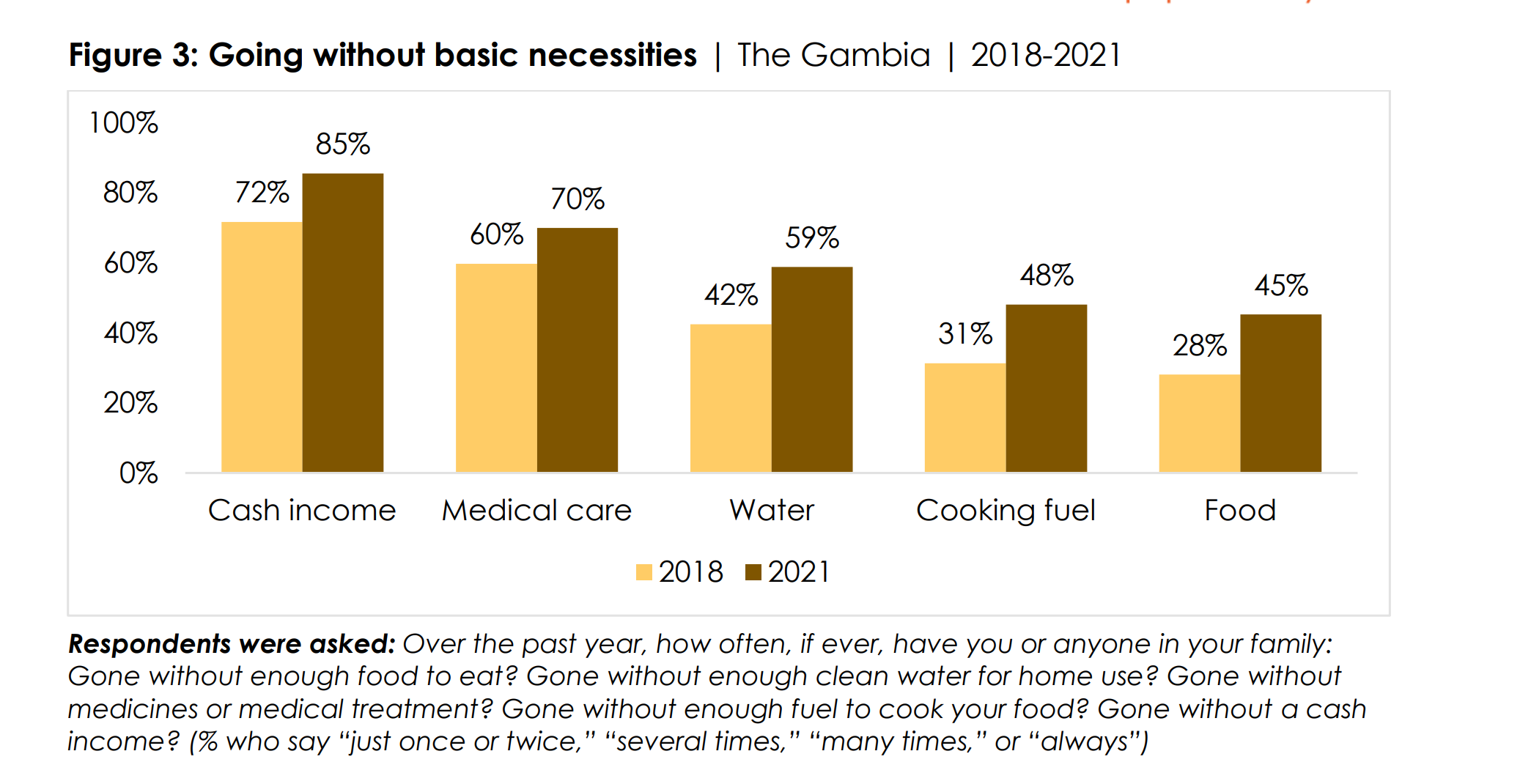

The recent Afrobarometer study reveals widespread perceptions of hardship and economic downturn among citizens.

Even though almost all the candidates have promised to improve the living conditions of citizens including the incumbent Adam Barrow, the apparent economic downturn poses a major threat to the sustainability of the media.

What is also threatening to the media are some of the repressive legislative remnants left behind by the Jammeh regime. Yahya Jammeh supervised the passage of many laws he used to silence the media and dissenting voices. President Adam Barrow has failed to repeal these laws despite promising to.

Still existing is the infamous section 138 of the Information and Communications Act which gives national security agencies, the Public Utilities Regulatory Authority and other state investigative bodies the powers to monitor, intercept and store communications for surveillance purposes. The law grants the bodies do these without any effective judicial oversight.

The Criminal Code of Gambia still contains clauses that prevent the exercise of the right to free expression. The criminal sedition relating to the President also still exists. It provides penalties including imprisonment for the president’s critics.

“There are still laws that are very bad with regards to the sedition against the president. He can use it if he wants,” Mohammed Bah revealed his fears about the laws.

Fake news, social media and the elections

Hours before the last presidential elections in 2016, Yahya Jammeh’s government shut down the internet including telephone connections.

“Internet in 2016 was a taboo,” Mohammed Bah said. “People struggled to get the internet. Government shut down the internet. People were struggling to connect. Now the internet is free and the speed has also increased a bit though it’s still a problem and it is accessible.”

Today, about 430,000 Gambians are on social media, which is a 16% increment compared to 2020. Internet penetration in the country has improved to 23%, according to the Data reportal. Afrobarometer reports that 65% of the citizens have social media as their source of information.

The growth and increasing usage of social media platforms have provided diverse opportunities for popular participation, particularly among the youth.

“Social media is the locus of contention. It is where most of these political debates are taking place, especially with the online media houses and also the individual influences. Social media is very crucial especially WhatsApp and Facebook. They have been used effectively by the political parties. Some of these political parties have their own Facebook TV and WhatsApp space where their share their videos and voice notes,” Sait Matte explained.

However, as the double-edged nature of social media will have it, the platforms are facilitating the spread of misinformation and disinformation.

“The social media have also become the platforms for the transmission or the distribution of fake news and those different issues which are very central to these elections,” Sait Matte noted.

Nearly 90% of the citizens believe social media is the foremost purveyor of false news ahead of politicians and political parties, government officials, and the news media and journalists.

These issues have resurrected concerns of whether the social media platforms should be interrupted ahead of the elections on Saturday, December 4, even though the government has so far not indicated any such intention. Many media stakeholders continue to caution the government against it. In an open letter to President Adam Barrow, Access Now called on the government to provide assurance against a shutdown.

“Ensure full internet access nationwide, and refrain from arbitrarily blocking access to social media platforms, and websites of media outlets; publicly assure the people of The Gambia that the internet and all other digital communication platforms, will remain open, accessible, inclusive, and secure,” the letter said.