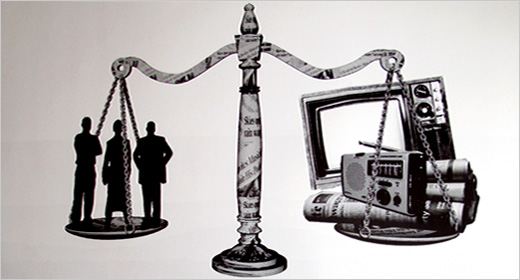

In recent times, West Africa has witnessed a troubling rise in the manipulation of various laws to target journalists, stifle dissent, and undermine press freedom.

Research reports produced by the Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA) on the legal obstacles to fighting impunity in six West African countries showed that while the repressive laws vary from country to country, a number of them are common to almost all the countries. These include defamation, cybercrime, national security and public order laws. Others are licensing regulations, insult laws and contempt of court.

Another common feature of these laws is that they are overly broad and ambiguously worded. They are often enforced selectively to stifle dissent, suppress accountability journalism, and intimidate critical journalists.

While these laws are ostensibly designed to regulate the media landscape and prevent misinformation, they are increasingly being weaponised by governments and powerful elites to intimidate critical voices.

Defamation Laws: defamation laws are used by individuals, corporations, or government officials to penalise critical reporting or commentary. While they provide a legitimate remedy for wanton and baseless attacks on corporate and individual reputation, defamation actions are often initiated by the powerful to bully their critics and save face. Defamation laws are often weaponised against journalists reporting on corruption or abuses to discourage further investigation. The threat of crippling damages, the high cost of litigation and the unpredictability of the courts sometimes force media houses to self-censor on certain critical or sensitive stories affecting powerful individuals or organisations.

Cybercrime Laws: cybercrime laws and electronic communications regulations are often invoked against digital journalists and bloggers for online publications or social media posts. Offenses like “spreading false information” or “misusing digital platforms” are broadly interpreted to target critical content. Such laws have been used to target journalists and activists, particularly in Nigeria.

Defamation and Cybercrime laws are the most formidable legal tools often used by individuals, corporations, or government officials to penalise critical reporting or commentary. Upon complaints from powerful organisations and individuals affected by critical publications, the police hurriedly arrest journalists on cybercrime and defamation charges. Many of these arrests are mischievous acts of harassment and intimidation. When the cases are actually sent to court, they turn out to be Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPP), instituted in bad faith to drain the defendants financially, morally and psychologically.

Section 24 & 27(1b) of Nigeria’s Cybercrimes Prohibition and Prevention Act of 2015 have been used to target journalists and activists, and the trend continues despite amendments effected in February 2024.

False publication and public order laws: Ghana’s recent fall in global press freedom ratings is largely on the back of serial violations perpetrated by invoking two laws that have become the substitute for criminal libel; Section 208 (1) of the Criminal Offences Act 1960, Act 29 and section 76(1) of the Electronic Communications Act (Act 775). The two laws penalise false publications likely to cause fear and panic with maximum jail terms of three and five years respectively. Over the past four years, they have been fully exploited to silence critics.

The Criminal Code: Togo’s report identified Article 497 (1-2) of Togo as serving the same repressive purpose as the above Ghanaian laws. This section of the Togolese law provides a pretext to apply criminal sanctions, including prison terms, for false publication offenses, although the Press Law of 2004 decriminalises press offenses.

The Digital Code: With regard to Benin, the Digital Code is the most commonly utilised legal weapon against critical online publications. It lends itself to the same repressive use as Nigeria’s Cybercrime law 2015 and has been used over the years to devastating effect.

Lèse Majesté or the offense of insulting the President and contempt of court laws have cost several journalists and media outlets serial suspensions in Cote d’Ivoire. Article 91 of the 2017 law governing the press maintains the offense of insulting the President of the Republic and authorises the closure of press outlets by the National Press Authority (ANP).

Similarly, Article 183 of the Penal code (Law no. 2021-893 of 21 December 2021) punishes the offence of ‘discrediting state institutions or their functions.’

In Guinea Bissau, widespread arbitrariness, physical attacks and intimidation have forced the media to practise self-censorship.

National Security and Anti-Terrorism Laws are applied to suppress investigative journalism on sensitive topics such as corruption, military operations, or human rights violations. Journalists and media outlets reporting on sensitive subjects are at risk of being accused of undermining national security or leaking classified information.

These weaponised laws underscore the need for a dispassionate review of the media laws and their application in order to address the overreach. The reports, therefore call for reforms to clarify and narrow the scope of such laws, along with improved legal protections for journalists.

You can click on Ghana, Nigeria, Cote d’Ivoire, Togo and Guinea Bissau to read the reports on these countries.