In this report, Programme Officer, Kwaku Krobea Asante, examines how social media, the internet, and mobile networks were disrupted in West Africa last year. The report also assesses the impact of the disruptions on the fragile democracies and weak economies of the region.

Last year, West Africa recorded at least five network disruptions in four countries. The disruptions happened in Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Senegal mostly during protests, elections, and social and political unrest.

Compared to the incidents that led to disruption in the previous year, 2020, where Togo, Guinea and Mali recorded five network interruptions, the data tell a story of unchanging narratives that are changing digital rights conditions in the region from bad to worse.

In 2021, network disruption in West Africa began in the Sahel, in Niger.

The internet was shut down on February 24, 2021, a day after the election management body announced the results of the second round of the presidential polls.

Nigerien news outlet, ActuNiger, reported that the internet blackout happened at the height of violent protests by supporters of the opposition party who suspected foul play by the Election Commission (CENI).

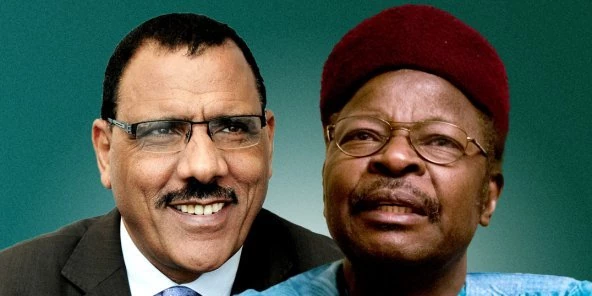

The Commission had on February 23 declared the incumbent President Bazoum Mohamed winner of the second round. But long before the declaration, the opposition had disputed figures from the CENI figures and denounced“an electoral hold-up”. Mahamane Ousmane, the leader of the opposition, is reported to have declared himself winner, erupting the vicious protests by the supporters in the capital, Niamey, and other cities. The violence resulted in vandalization of properties and mounting of barricades on the road.

The government arrested over 470 protestors. Two of them were killed, the country’s Minister of Public Safety confirmed in a statement on television. The four major internet service providers (ISPs) in the country were disrupted.

The internet disruption lasted 11 days. But its impact on the already fragile democracy, poor human rights record, and the economy of the country, considered one of the poorest in the world, will be lasting.

The disruption in Niger had not ended when Senegal’s took off on March 5, 2021.

For the most part of the last decade, Senegal had remained a poster child for freedom of expression, press freedom, and many other democratic ideals in the West Africa region. But early last year, the country hit a ditch and tumbled. And it was a huge fall, one that saw the killing, arrests, and detention of protestors, and the closure of media outlets. Thus, the disruption of the internet was a culmination of many other freedom of expression violations.

It began with the arrest and detention of Ousmane Sonko, one of the loudest critics of the government, and leader of the opposition political party Patriotes du Sénégal pour le Travail, l’Ethique et la Fraternité́ (Pastef-Patriotes). Sonko, 47, who’s also a member of the National Assembly, came third in the 2019 presidential elections, garnering 16% of votes cast.

He was charged with “disturbing public order and participating in an unauthorised demonstration” while also responding to rape charges.

Sonko was arrested on March 3. This resulted in the breaking of violent protests by his supporters across the capital, Dakar, and other major cities including Kaolack, Saint Louis, and Casamance. The demonstrations persisted on March 4. The internet was disrupted the dawn of the next day, March 5. It was restored by morning, UK-based Netblocks, which tracks Internet disruptions globally, confirmed in a statement.

⚠️ Confirmed: Social media and messaging apps restricted in #Senegal amid political unrest following arrest of opposition leader; real-time metrics show Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp and Telegram CDN servers disrupted, limiting photo and video sharing 📉

📰 https://t.co/klvokfpLyu pic.twitter.com/L6q3ygu9jP

— NetBlocks (@netblocks) March 5, 2021

On June 4, 2021, Nigeria’s Minister of Information and Culture, Mr Lai Mohammed, announced that the country had banned Twitter. He published the statement on the ban on social media including Twitter, drawing a lot of humour from users of the platform. The announcement was, however, a serious one.

“The Federal Government has suspended, indefinitely, the operations of the microblogging and social networking service, Twitter, in Nigeria,” the statement announcing the ban said in part.

The Minister added “the persistent use of the platform for activities that are capable of undermining Nigeria’s corporate existence”.

The immediate trigger to the government’s decision to ban the platform was Twitter deletion of a tweet by Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari two days before. President Buhari, a Fulani man and former military leader of the country, reacting to violent protests by a secessionist group in the southeast region of the country had evoked Nigeria’s civil war experience. The Biafra War, as it was called, was fought between 1967 and 1970 where millions of Igbos, an ethnic group in the southeast, were reportedly massacred.

In his tweet, President Buhari threatened to deal with secessionist group for the “misbehaviour” adding “those of us in the fields for 30 months, who went through the war, will treat them in the language they understand”.

The tweet drew a barrage of condemnation, with some Nigerians calling for the President’s account to be suspended. Twitter found the tweet a violation of the platform’s policy and hence deleted it.

The remote cause of the ban, some analysts say, was Twitter’s support for the #EndSars protest, a nationwide demonstration, mainly by the youth, against police brutality. The Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) had been accused of rampant extra-judicial killings, extortion, and other abusive acts against young Nigerians. During the protests in November 2020, Twitter designed a logo for the campaign while its CEO, Jack Dorsey, solicited for donations at the chagrin of the government whom the protests made unpopular.

The ban on Twitter in the most populous country in the West Africa lasted for over half a year, having been lifted in January 2022. It left lasting impact on many citizens especially business people, right activists and journalists who use the unique opportunity the social platform provides to reach out to their clients, communities and sources.

“Information and contacts that one would have easily accessed on Twitter became difficult to get as a result of the ban,” Innocent Duru, a journalist with the Nations Newspaper shared the impact of the ban on his work with the Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA).

“Twitter gave me the opportunity to get in touch with those who share information on the platform to do a follow-up. This has not been possible following the ban. Also, I previously used to get people to interview on Twitter. This has not been possible again,” he added.

In September, Authorities in Nigeria shut down mobile networks in Zamfara State in the North, citing security reasons.

The mobile network disruption followed the kidnapping of 73 children from a school by a criminal gang locally known as ‘bandits’. The Communication Commission in a letter addressed to a telecom service operator said, “the pervading security situation in Zamfara state, has necessitated an immediate shutdown of all telecommunications services… for two weeks.”

The letter added that “this is to enable relevant security agencies (to) carry out required activities towards addressing the security challenge in the state.”

According to TOP10VPN, UK-based internet research organisation, disruptions in Nigeria affected 104 million people and cost the Nigerian economy a total cost of $1.5 billion.

Two months after the Zamfara State blackout, another internet blackout occurred in the Sahel, this time in Burkina Faso. The country which has been battling terrorist attacks from Islamic militants in some of its regions shut the internet amid political unrest.

A week before the shutdown, suspected Islamist militants had attacked a military post in Inata near the northern border with Mali, killing 53 people. The incident triggered nationwide demonstrations.

On November 20, in Kaya, 100 km north of the capital, Ouagadougou, some of the demonstrators directed their anger towards the presence of French military troupes in the country, deploring the control of the French in the country.

The troupes were reportedly present as part of efforts to fight against the Islamist rebels in the region. A French military convoy passing through the Kaya town en route to Niger, reports indicate, met barricades on the road mounted by the protestors. The convoy shot at the demonstrators, fueling the already flaming protests. By 10:30 pm in local time, mobile internet connectivity was disrupted.

⚠️ Confirmed: Mobile internet has been disrupted in Burkina Faso since Saturday night.

The incident comes amid unrest after the shooting of protesters attempting to block a French military convoy transiting the country 📵

📰 Report: https://t.co/izYzlPUU19 pic.twitter.com/kdKmLZexzS

— NetBlocks (@netblocks) November 21, 2021

“This class of internet disruption cannot be worked around with the use of circumvention software or VPNs. Fixed-line and wifi services appear largely unaffected by the disruption, although most users are reliant on mobile phones,” Netblocks explained the nature of the interruption.

Two days later, November 24, the Ministry of Communication and Relations with Parliament confirmed the shutdown, citing legal requirements for “national defense” and “public safety”. They extended the shutdown by 96 hours. On November 26, it was further extended for another 96 hours.

ℹ️ Update: Burkina Faso's government has extended the national mobile data shutdown by another 96 hours.

Service was cut on Saturday night and was due to resume earlier today. The information blackout comes amid anti-government protests.

📰 Report: https://t.co/izYzlPUU19 pic.twitter.com/2e0rMYqSV6

— NetBlocks (@netblocks) November 24, 2021

After a week, the internet was restored. But the country lost in many ways. In monetary terms, Top10VPN estimates $35.9 billion as the total cost of loss.

Meanwhile, Burkina Faso has become the only country among the four to repeat the gross violation of its citizens right to information this year.

On January 23, 2022, a day before the coup that ousted President Christian Kaboré’s government, mobile internet was cut for 35 hours amidst heavy-handed policing against anti-government demonstrations.

If the sub-region was plunged into digital blackout in 2021, it appears to be emerging into light in 2022. Halfway through the year already, the 35-hour shutdown in Burkina Faso in January remains the only setback.

It goes without saying that, shutting down the internet and blocking means of communication is a flagrant abuse of human rights and is at variance with many international human rights standards.

In this age when having the internet is synonymous with being able to speak and see, shutting them down is a weapon fit for only authoritarians. Rightly so, Access Now called their 2021 report on internet shutdowns the return of digital authoritarianism.

This disturbing phenomenon was the focus of a May 13, 2022 report by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Titled Internet shutdowns: trends, causes, legal implications and impacts on a range of human rights, the report said Internet shutdowns “most immediately affect freedom of expression and access to information – one of the foundations of free and democratic societies and an indispensable condition for the full development of the person.”

“When States impose Internet shutdowns or disrupt access to communications platforms, the legal foundation for their actions is often unstated. When laws are invoked, the applicable legislation can be vague or overly broad,” the report added

The Media Foundation for West Africa shares the above concerns about the four internet disruptions recorded in West Africa in the course of last year. The internet is the lifeblood of several businesses, socialization, education, and research. Its interruption can be a matter of life and death for some businesses and individuals. It affects a country’s economy and undermines investor confidence. We, therefore, urge governments in the sub-region to see the internet in the same light as the national power grid and avoid disrupting it at the least opportunity.